It is strange to talk about black or blackness when the color refers to the absence of visible light. In a sense, we know it through absence. If black is the absence of light, it’s difficult come up with an image of it. We ‘see it’ best only in relation to things we can see such as the saguaro cacti in the image below.

I used a digital infrared filter for this photograph taken near my home in the style of Anselm Adams. The sky appears black because the filter blocks visible light, something we see only because of the earth’s atmosphere. Once an astronaut leaves the earth’s atmosphere, space looks very much like the sky in my photograph.

One clear night in the Sonoran Desert, I pointed my camera up towards the dark sky and took a photograph without any special telephoto lens. The result was a black image with thousands of scarcely visible pinpricks of light. These faint pinpricks were stars in the 13.5-billion-year-old Milky Way galaxy, the galaxy within which I stood. The sky appeared black because in space there is no atmosphere to scatter light.

To produce the image above, I cropped out a very small part of my original photograph then enlarged it very significantly and increased its brightness. The result was this collection of different colored circles of light against a black background. These are about twenty of the more than 100 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy which is only one of more than 100 billion galaxies in the universe. The different colors of stars are a result of their temperatures, chemical compositions, and the physics of light. Cooler stars appear red, while hotter stars can appear blue or white. The gold color of stars is a result of their composition, which includes heavy elements like gold and platinum. These elements are produced in supernovae and neutron star mergers, a process known as the r-process. The gold-rich stars today are essentially the remnants of ancient galaxies that merged with the Milky Way over 10 billion years ago.

This is a Phainopepla. The word phainopepla comes from Greek meaning “shining robe,” referring specifically to the male birds sleek, reflective black feathers.

Phainopeplas are primarily found in the deserts and arid regions of the southwestern United States, from central California in the north to the Baja peninsula and central Mexico along the interior Mexican Plateau in the south. Their movements are influenced by the availability of berries that they find in desert washes, mesquite groves, and oak and sycamore woodlands. They are common in our Southern Arizona neighborhood, distinguishing themselves from other birds by the black color.

Here’s another black creature found in nature. The skunk’s black color is accentuated by its white stripe. It is a nocturnal animal and difficult to see at night. The word “skunk” was used in the Algonquin language in the early 1600’s. A description can be found in the Jesuit Relations, chronicles of the Jesuit missions (Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France) in the mid seventeenth century:

“It has black fur, quite beautiful and shining; and has upon its back two perfectly white stripes, which join near the neck and tail, making an oval that adds greatly to their grace. The tail is bushy and well furnished with hair, like the tail of a Fox; it carries it curled back like that of a Squirrel. It is more white than black; and, at the first glance, you would say, especially when it walks, that it ought to be called Jupiter’s little dog. But it is so stinking and casts so foul an odor, that it is unworthy of being called the dog of Pluto. No sewer ever smelled so bad. I would not have believed it if I had not smelled it myself. Your heart almost fails you when you approach the animal.”

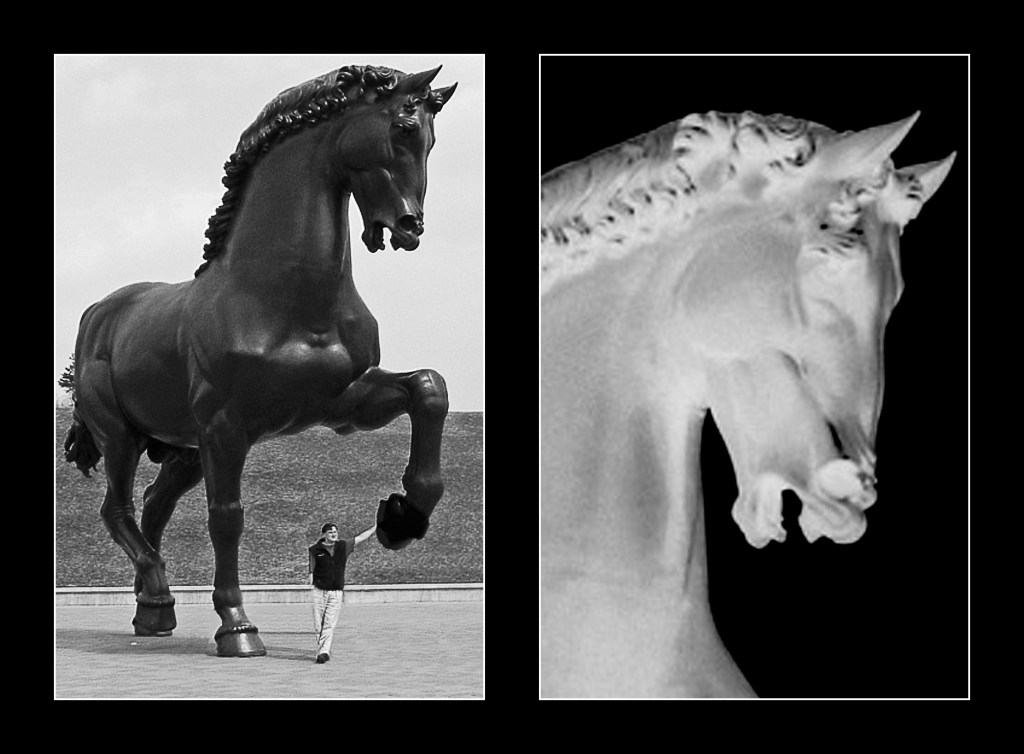

This sculpture in Michigan in the United States has its origins that date all the way back to 1482! Leonardo da Vinci first envisioned a horse sculpture for the Duke of Milan and sketched a rearing horse with a rider. Despite years of preparation, da Vinci’s designs for the towering bronze piece never materialized and the bronze originally intended for the sculpture was repurposed into military cannons in 1494.

In 1977, American art collector Charles Dent embarked on a 15-year journey to complete da Vinci’s vision and bring this masterpiece of a sculpture into existence. The sculptor Nina Akamu redesigned the piece creating two casts for the final bronze sculpture after Dent’s death in 1994. In 1999, the first bronze cast of Akamu’s stunning black beauty design was placed in Milan and the second cast was used for the American Horse sculpture depicted here with my son.

In the bright afternoon sun, the interior of the parking garage looks black. There seems to be a complete absence of light inside the building. Unless one has entered previously, one has no idea what the garage looks like inside. In prehistoric times, an early human might have been fearful about entering a dark cave, not knowing what danger to expect. Today, we generally know what to expect in a parking garage, but a deep-seated fear of the dark lurks somewhere in our inherited psyche.

And now for something different. In this photoshopped image of mine, three witches scurry away in a desert wash. In the foreground, a dark shape broods menacingly.

Black was one of the first colors used by artists in Neolithic cave paintings. It was used in ancient Egypt and Greece as the color of the underworld. In the Roman Empire, it became the color of mourning, and over the centuries it was frequently associated with death, evil, witches, and magic.

We may not have any good reason to fear the dark as our neolithic cave-dwelling ancestors might have. Black is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness, the opposite of good, evil. Even though this image is simply a photograph of a motel, my treatment of it introduces something sinister, something we know nothing about, but which leaves us feeling uneasy

Not wanting to end this post on such a dark note, here is something more upbeat:

The sky is black. Ideal for watching the fireworks over the Danube on St. Stephen’s Day in Budapest.