The danger of flying is the sense of detachment it brings from life on the ground

In 1953, I flew in a Pan American World Airways DC-6 from South Africa to Boston. It was the first of many long-distance flights that included flying on a BOAC Comet to Heathrow, and with Air China on an old Boeing 747 from Los Angeles to Shanghai. There was one memorable east-to-west around-the-world flight mainly on Quantas and north-south flights to Jamaica, Mexico, Brazil, Barbados and South Africa. And too many flights to Europe to count. One thing didn’t change: The view of the sky and clouds.

I liked a window seat so that I could turn away from the coach with its crush of passengers and video screens and look out at the clouds, but often with the guilt that sometimes accompanies the feeling of detachment from the real world below.

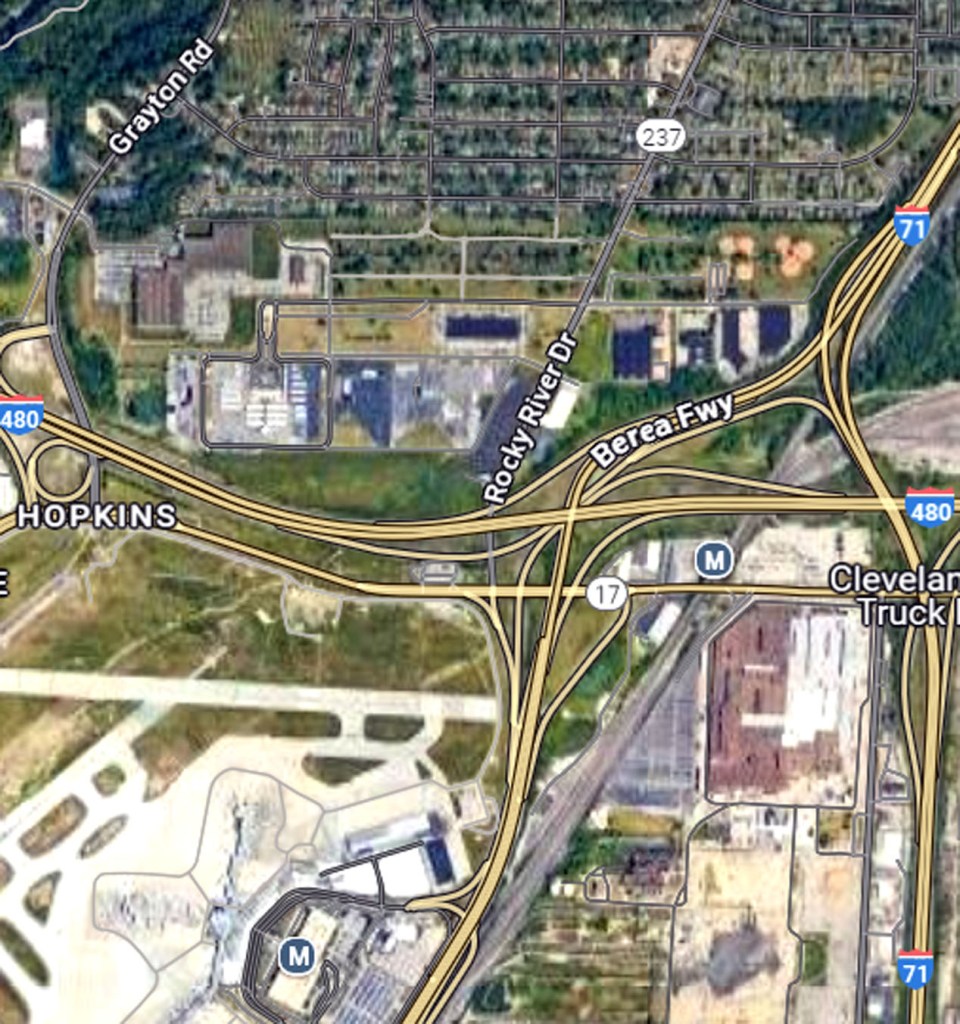

I recall flying home late one afternoon and, on the final approach, looking down at the little houses in the blue-collar neighborhood laid out on a grid of tree-lined streets squeezed in between highways and runways.

In an instant, I saw a family in each house with each member bringing home a sliver of the multiplicity and complexity of their lives outside the home: The teenager, a mother, a father. And a great compression of the larger worlds of which they are a part into the little structure that for now is home. Each house, a different family; each a little world to itself. A few hundred homes.

And from the plane, I watched cars moving on the streets, most coming home, some leaving: Each story the same, but different. Beyond the streets and trees and houses, the highways came into view with rush-hour traffic heading west and east and branching off to the south.

And, in that instant, I saw a sense of purpose in all the vehicles speeding in opposite directions, and all cars turning into the driveways of different houses in the little neighborhood.

And in the sky above, an unseen network of satellites provides location guidance to the drivers and the ability to call home to say that one will be late. And as a look down, I see a dynamic system at play, not comprised of autonomous agents, but a system of interdependent elements whose very existence is contingent on the system as a whole.

And I become conscious of the approaching runway and the other aircraft, some departing and others at the terminal, and I recognize that I’m not an observer of the scene below, but a participant in it, an element in the larger self-correcting system that shapes and is shaped by its parts.

And the words of my uncle George come to mind as he describes his experience looking down from a mountain at the village below:

And the streetlights come on, and a kettle whistles on the stove, and in a home a small child feels safe and secure. And yet … and yet.

John,

I appreciated your liking my Contemplative Photography posting. Your writing as well reflects the thinking of Teilhard de Chardin, whose writings have been fundamental to my spiritual development since 1960. Have you seen Brian Swimme’s book, The Story of the Noosphere? Beautiful book as well as insightful. He too has been strongly influenced by Teilhard. Also, check out Spiritual Visionaries.com where I posted several videos of futurist Barbara Marx Hubbard. She, more than anyone else, articulated Teilhard’s vision of a positive future—the process of Christogenesis. If you like, I can be reached at smithdl@fuse.net

LikeLike