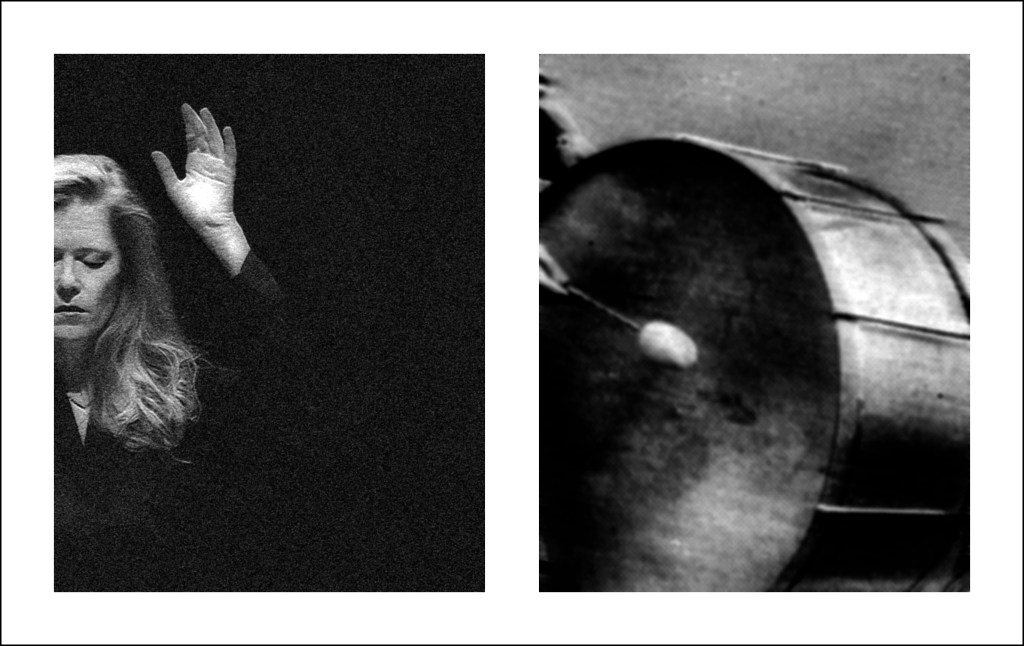

Left: Mango Tree & Music Right: Lilian, South Africa, 1972

Resurrection

My girlfriend liked Mahler,

his second symphony:

She listened to it often, so I did too.

It made her think of the child she lost.

It made me think of her,

so I bought the record for myself

and played it looking out of my

apartment window at a mango tree.

I thought, ‘this is the only place in the

universe where Mahler’s music floats

among the branches of a mango tree.’

The Resurrection

is what they call the Second.

These long years later,

I listen to it, and every time

I feel her pain,

and watch the mangos

as they slowly ripen.

Fifty-two years later:

Left: Severance Hall, Cleveland. Right: Lilian viewing Mahler score

The Cleveland Orchestra owns the only complete, original, handwritten score of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony no. 2. Mahler wrote it between 1888 and 1894 in his characteristically bold musical script, mainly in intense black ink, with some parts in brown or violet. It is a working manuscript with inserted leaves, corrections, deletions, and revisions. It was purchased by Herbert Kloiber, a trustee of the Cleveland Orchestra, for about $6 million in 2016 and donated to the orchestra.