Through the eyes of a contemplative photographer

A visit to an art museum can be a contemplative experience if one has time to be still. One is less likely to have this kind of experience in busy museums like the Louvre, the Duomo, the Met and MOMA than in smaller local galleries. A camera can help one focus on the here and now as long as one doesn’t click at everything one sees. It can help one pause and look below the surface of things. Here’s an example:

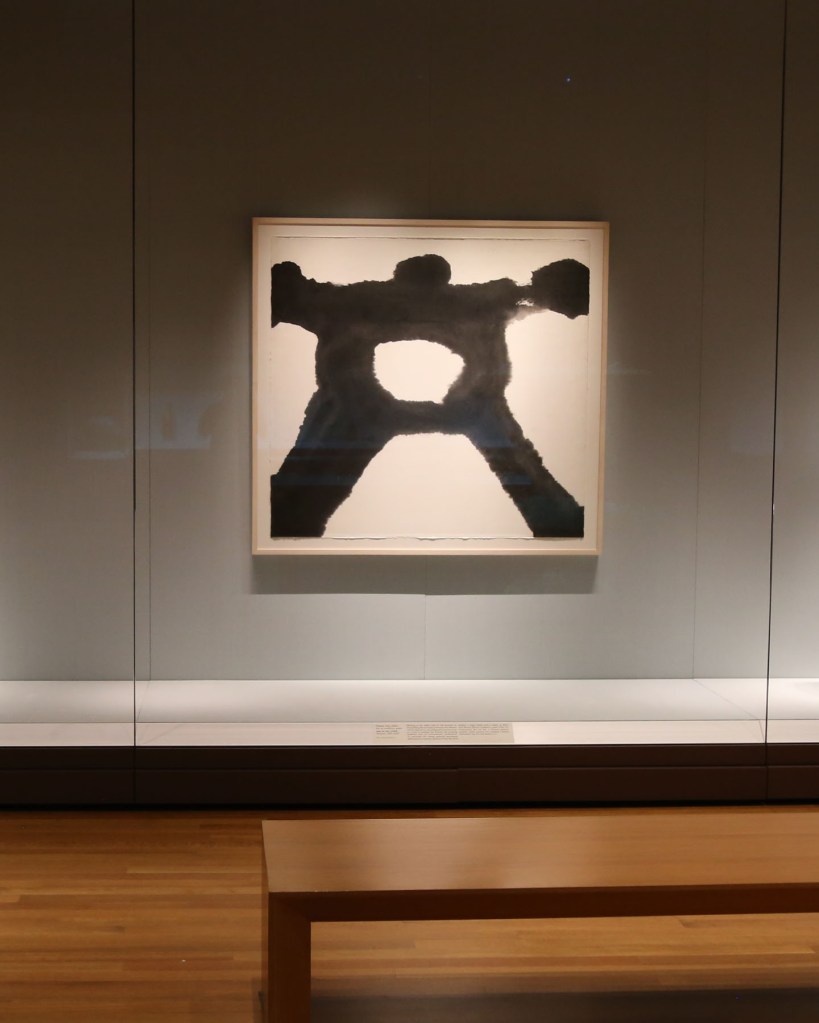

Person, early 2000s. Suh Se Ok (Korean, 1929–2020).

130.5 x 139 cm (51 3/8 x 54 3/4 in. Ink on mulberry paper

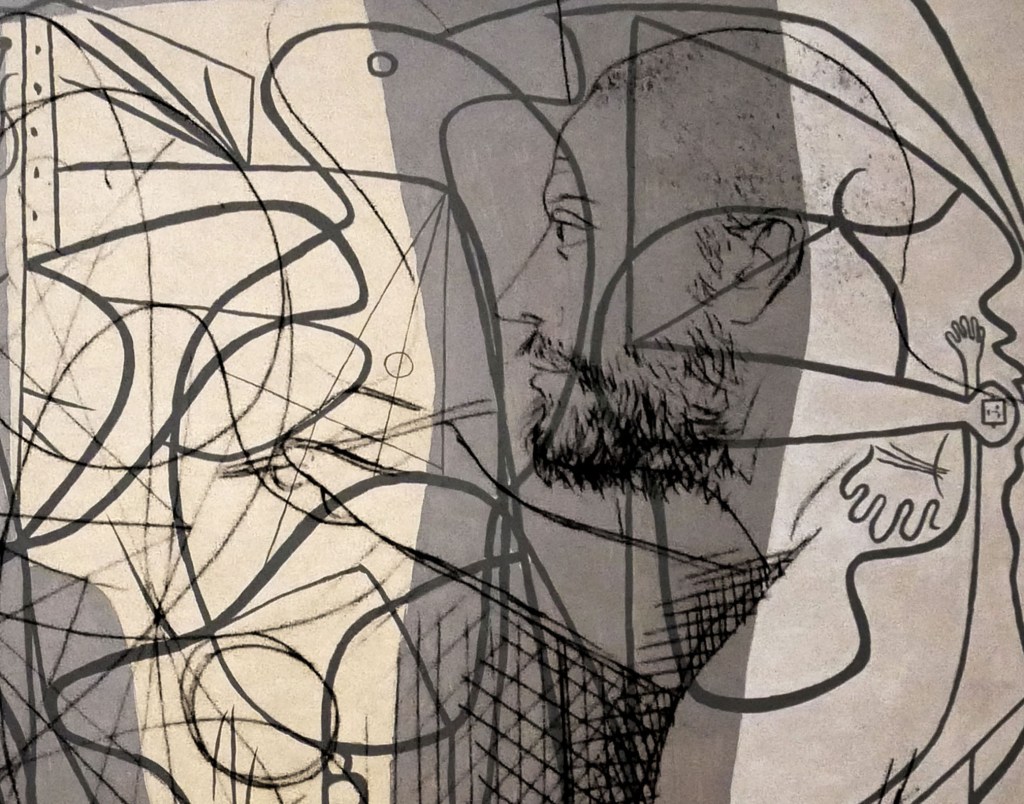

I’m alone in the gallery together with Suh Se Ok’s “Person”. It is mysteriously expressive: A cry for help, perhaps. Or an invitation for unity.

Back at home, I modify the image.

The image has clearly evoked something below the surface even if I’m not entirely sure what it is.

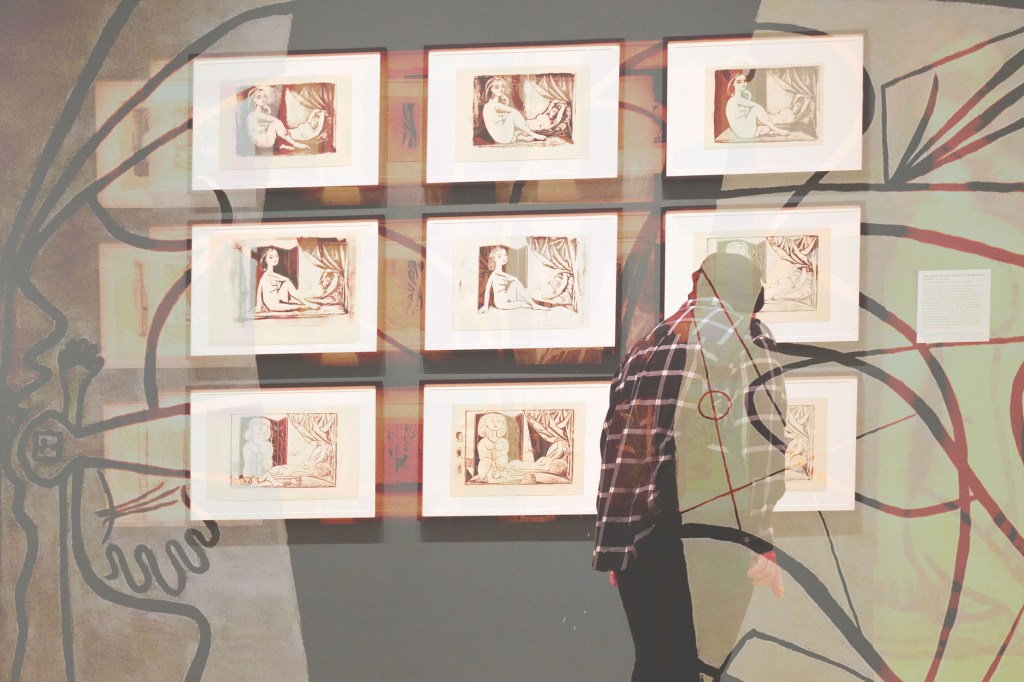

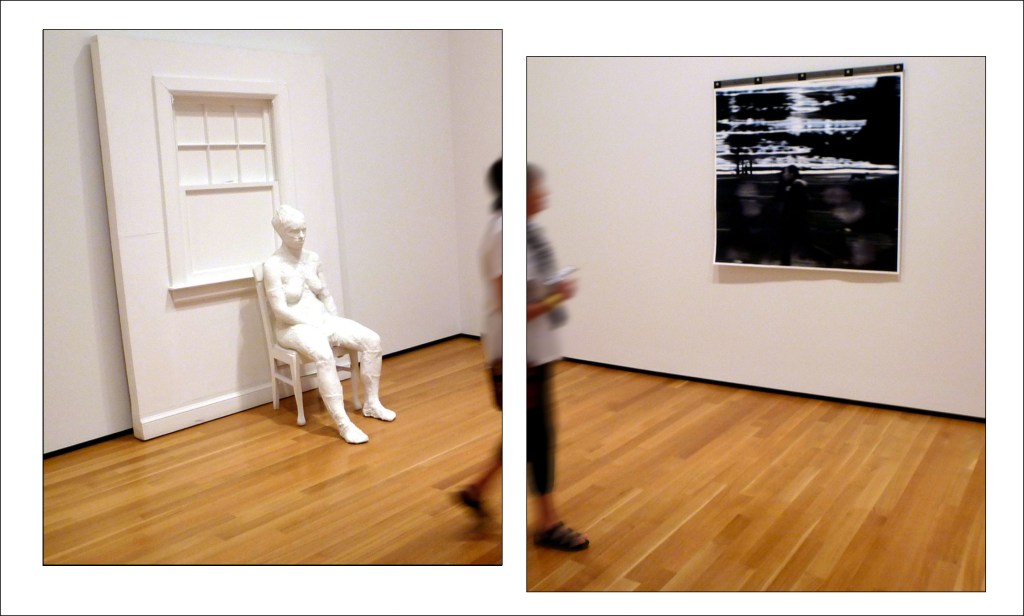

Other images are less obscure as I introduce some movement into them:

Lilian steps out of the space she occupied with seated sculpture into a new space in which she will engage with the somber abstract painting.

And again, below, the relationship between a human subject and an artistic installation stimulates an emotional response. Scale, color, and movement create a sense of foreboding.

Below is another photographic, a diptych. It tells a story combining past, present and future.

On the left, an older person sits between paintings of birth and death. The image of the crucifixion projects a narrative of suffering and redemption. It was the explanation that many of us were given as children. It speaks of suffering in the human condition and, even though we were taught about salvation, there is nothing in the image to suggest it. And so, she sits in silence at the foot of the cross.

The second panel in the diptych portrays a group of school children on a trip to the museum. There is movement. They are bathed in light. They don’t sit and ponder but run and explore. Perhaps they won’t be told the same stories with which we grew up. Perhaps they will write their own stories.

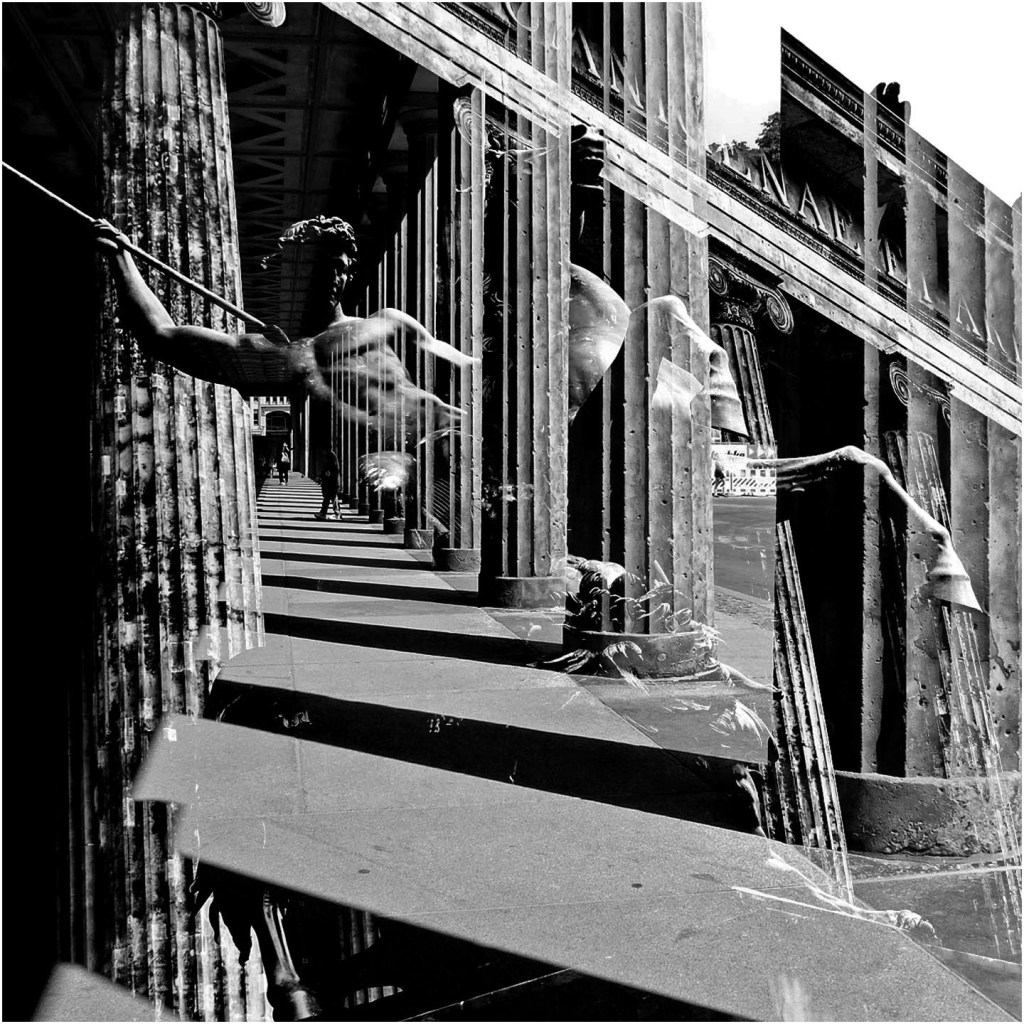

Let’s visit the Altes Museum in Berlin where the Neoclassical façade consists of a portico with Ionic columns and, on the steps in front of the museum is an 1858 bronze statue, The Lion Fighter, by Albert Wolff. I have combined two photographs to integrate the two ancient perspectives.

And in the Pergamon museum, a young woman is absorbed drawing one of the Ionic columns.

She is oblivious of the crowds around her, in the moment, at one with the ancient column whose form and beauty transcend time.

There is a different oblivion in the following photograph I took at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Their absorption in each other involves, perhaps, a mutual sense of transcendence that one sometimes experiences in an art gallery.

A museum experience may not always be profound, but later to dwell on the photographic image quietly for several minutes brings its own reward.

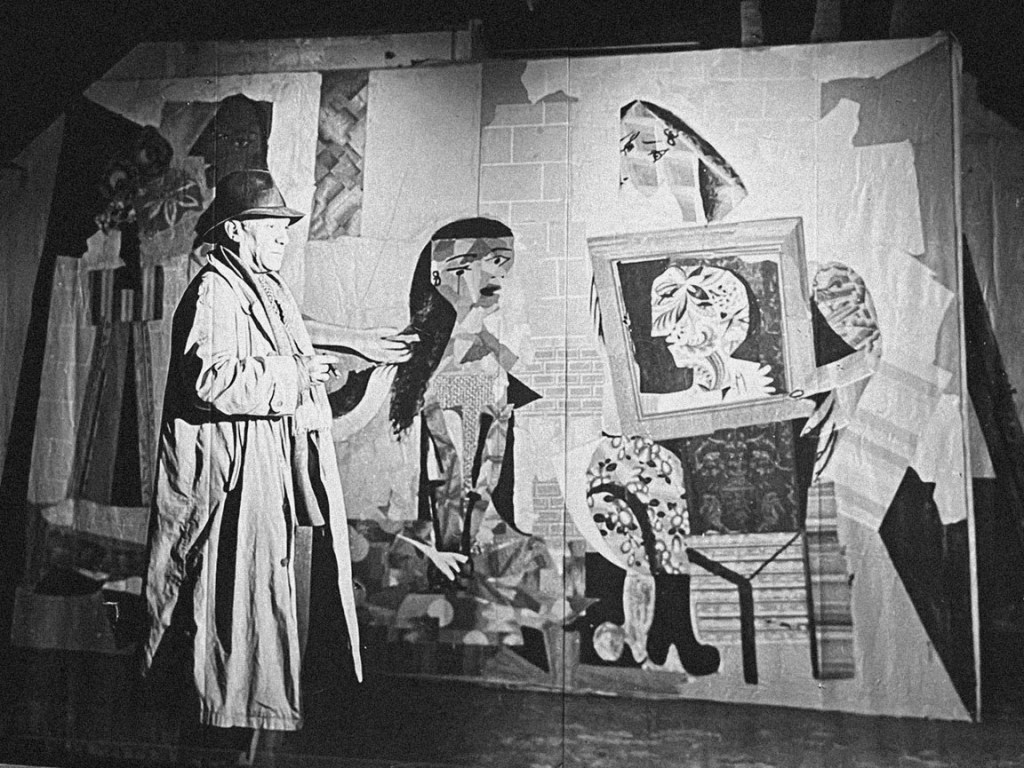

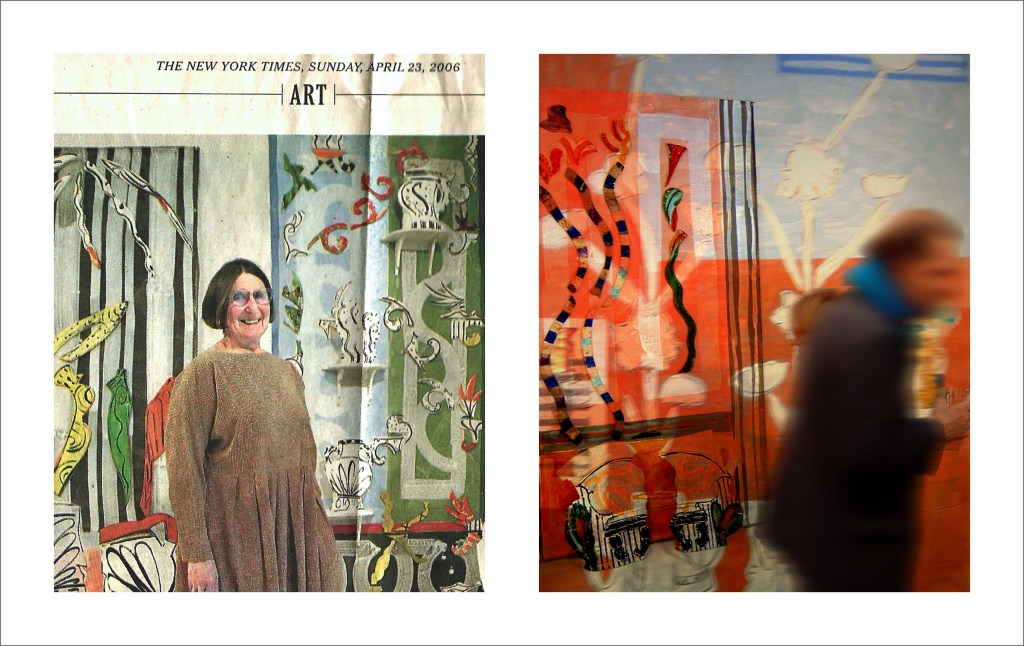

While thinking of color, I’m reminded of my aunt, Betty Woodman, a ceramicist, who nearly twenty years ago exhibited her work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

On the left is part of a newspaper clipping from the time, and I created the panel on the right by superimposing two photographs, one I took at the vernissage, and the other taken in her studio.

Returning briefly to the contemplative experience in the museum, the following unedited image of a man reading the art label conveys a sense of respect for the subject.

The Lady of Carthage mosaic (4th-5th century)

Engagement is another museum experience when the viewer is drawn in by the subject.

The doppelganger effect of the reflection in the glass door creates the illusion of a detached person observing the interaction, the unity of sorts, between the sculpture and the viewer. This raises the issue, perhaps, of the tension between detachment and engagement in our own day-to-day lives.

Some experiences are difficult to express through photographic manipulation. Take, for example, the following painting:

Honors Rendered to Raphael on His Deathbed: Pierre- Nolasque Bergeret: 1806

The painting hangs in Oberlin University’s Allen Museum of Art. I was particularly struck by it, not because it is an excellent example of the late eighteenth century tradition of depicting deaths of historical figures, not because it depicts Pope Leo X and an assemblage of notable figures including Michelangelo and the writer Vasari, but because the painting’s nineteenth century owner was Joséphine de Beauharnais.

Napoleon purchased the painting for his empress Josephine at the Paris Salon in 1806, and she hung it at her Château de Malmaison. As I gazed at the painting, I became acutely aware of the fact that this same piece of canvas just three feet in front of me with all its layers of oil paint carefully applied by Begeret was admired by Joséphine more than two hundred years ago. It was as if she was standing alongside me, both of us looking at the same painting, two viewers unable to find any common ground for communication across the centuries but both silently contemplating the striking image together.

I’ll end this stream of consciousness posting with a few more photographs:

In the left panel, a ray of sunlight streams through the open door of my Montreal office many years ago. The right panel contains a corner of the waiting area.

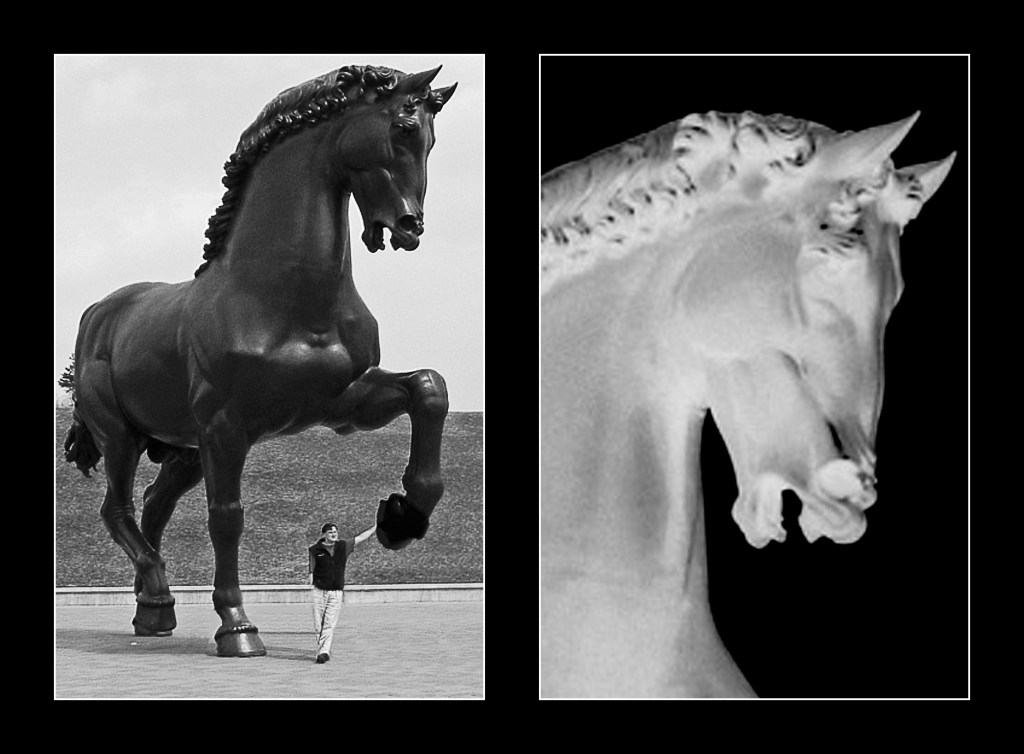

Da Vinci’s Horse, Grand Rapids, Michigan

In the late fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci embarked on a project to create the largest equestrian statue of his time. But the bronze earmarked for this sculpture was repurposed for warfare. Centuries later, sculptor Nina Akamu revived the project, and in 1999 two casts were poured, one finding its way to Milan, and the other making its home in the United States.

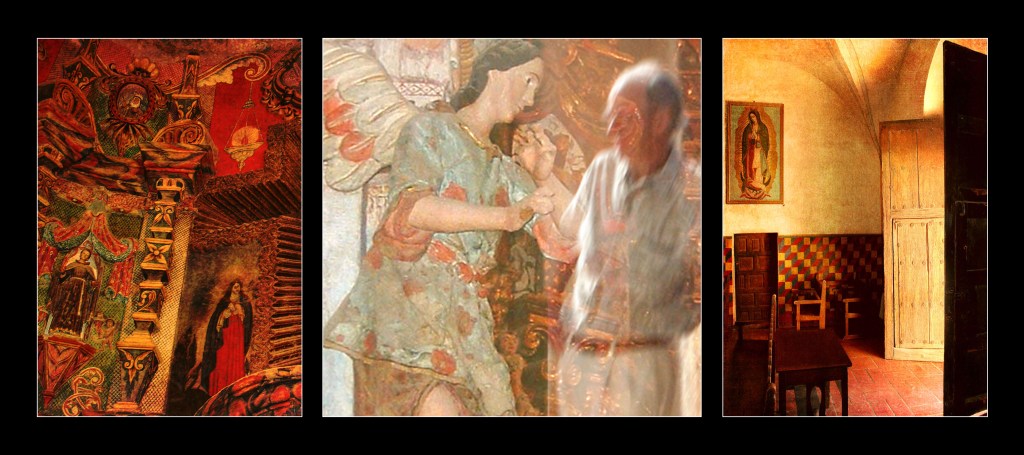

Finally, the photographer wrestles an angel in the church of Xavier del Bac, the Spanish mission founded in 1692 by Padre Eusebio Kino, an Italian Jesuit who traveled from Europe to the “new world” in the late 17th century.

c