Oranges fresh from our orange tree in Arizona

There is something about picking oranges each year until there are none left, except a few that are too high to pick, that puts one in a contemplative frame of mind.

” Ambrosia” or Nectar of the Gods is how Lilian describes our morning orange juice

I would often walk out to the orange tree in our side yard and pick four or five of the fruit to squeeze for Lil and myself. I was struck by the fact that the juice, still cold from the night air, was still living in its cellular processes. Up until a few minutes earlier, it had been absorbing water, sugar and other nutrients through the trunk; organic compounds from its leaves; and reliant upon the millions of delicate, microscopic root hairs underground that wrap themselves around individual grains of soil and absorb moisture along with dissolved minerals. A process of respiration was constantly underway in the tree’s cells absorbing CO2 and releasing the by-product of photosynthesis, oxygen, into the atmosphere. As I stood beside the tree, I was struck by the likelihood that I was inhaling atoms released through its leaves. And, as the tree released oxygen, carbon dioxide, and moisture, it sucked up large amounts of water from the ground. And the moisture came from the same sources upon which I relied to live; water from the underground aquafer as well as the Central Arizona Project, a 336-mile aqueduct that diverts water from the Colorado River to cities and farms in Southern Arizona. We are also united by our need for nutrients: Chemical elements such as sodium, potassium, chlorine, calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus that come ultimately from the soil and pass up the food chain from plants to humans. There is more to the orange tree that vitamin C.

And, as I sipped my morning juice, I thought of an evolutionary chain going back fifteen million years when citrus plants diverged from a common ancestor and I realized that, in the great sweep of evolution and human history, it was only yesterday that the Spanish Conquistadors introduced oranges to North America. I wonder if they tasted the same.

An orange in our Ohio supermarket

I noticed the label on an orange in the nearby supermarket. A sunny day came to mind with the image of an orange tree in South Africa where we lived and the image of a person picking the fruit then magically handing it over to us. A sharp citrus aroma escaped as Lil cut into the skin. She offered me a wedge and I had to acknowledge that it was extraordinarily sweet. Nearly as moist and sweet as our Arizona oranges. Curious about the label on the fruit, an internet search revealed that PLU#3156 referred to a refrigerated shipping container on a ship off the coast of Cape Town.

Oranges as commodities

The refrigerated containers were filled with oranges that had been picked a thousand miles to the north. They had been packed, not gently by hand into small wooden boxes, but by robotic arms in an automated warehouse the size of a football stadium, then chilled to a temperature just below freezing and loaded with 750 other containers onto the ship. They were stacked five high on the deck, then transported eight-thousand miles on a three-week voyage to Philadelphia where, together with other containers they would be shipped to dozens of distribution centers across the US. one of which is in Grove City, Ohio, where cartons of oranges would be loaded into trucks and distributed to supermarket locations throughout the state including our local store.

As I peel the perfect four-week-old South African orange, I’m reminded of our years in Jamaica:

Despite its mottled appearance and difficulty to peel with a knife, the Jamaican orange is sweet and juicy, and typically sucked rather eaten. And I remember the rough, bumpy-skinned Ugli fruit, the Jamaican Tangelo, a cross between a mandarin orange and a grapefruit with a sour-sweet taste.

Did we miss our morning juice from our years in Canada?

In Canada when fresh oranges were expensive, our daily source of vitamin C was reconstituted frozen orange juice concentrate. Yes, we were getting our vitamin C but, at the sensory level, there was no organic connection. The organic connection with the fruit in South Africa was restored during our years after Canada in Jamaica.

But the mind keeps returning to Arizona:

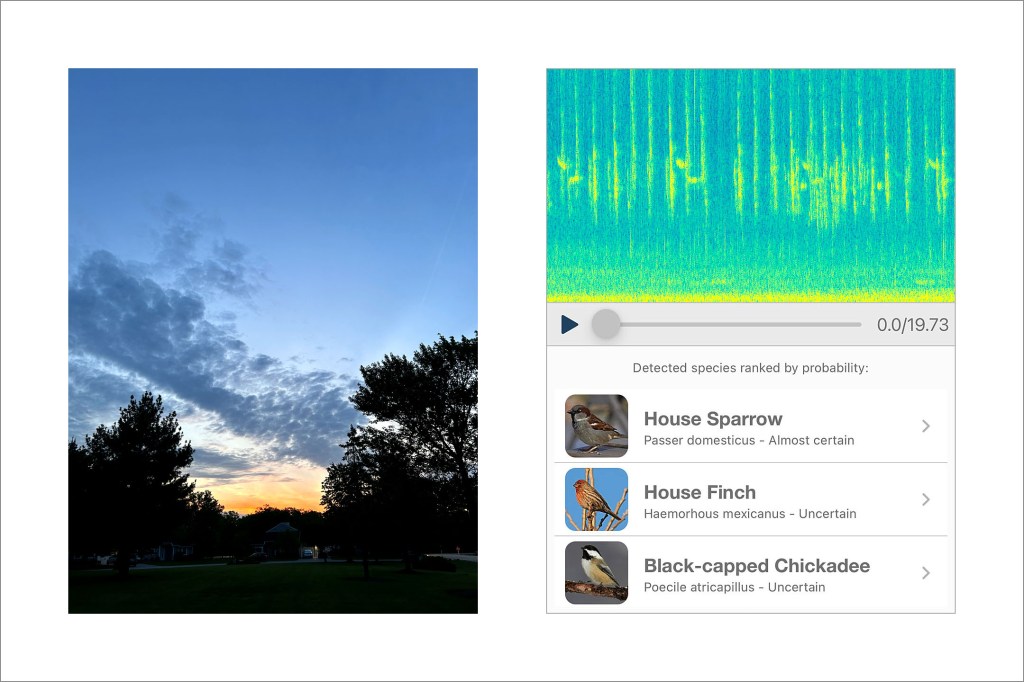

Through the kitchen window

Taken from outside our home during a hot summer night in Tucson, the image holds out the promise of a new day when the oranges in the bowl will be squeezed to link us closely to our environment. And so it goes.