The fifth in a series looking around our home at the paintings, prints and objects we have picked up over the years, not because they are of any particular value other than that we enjoy them

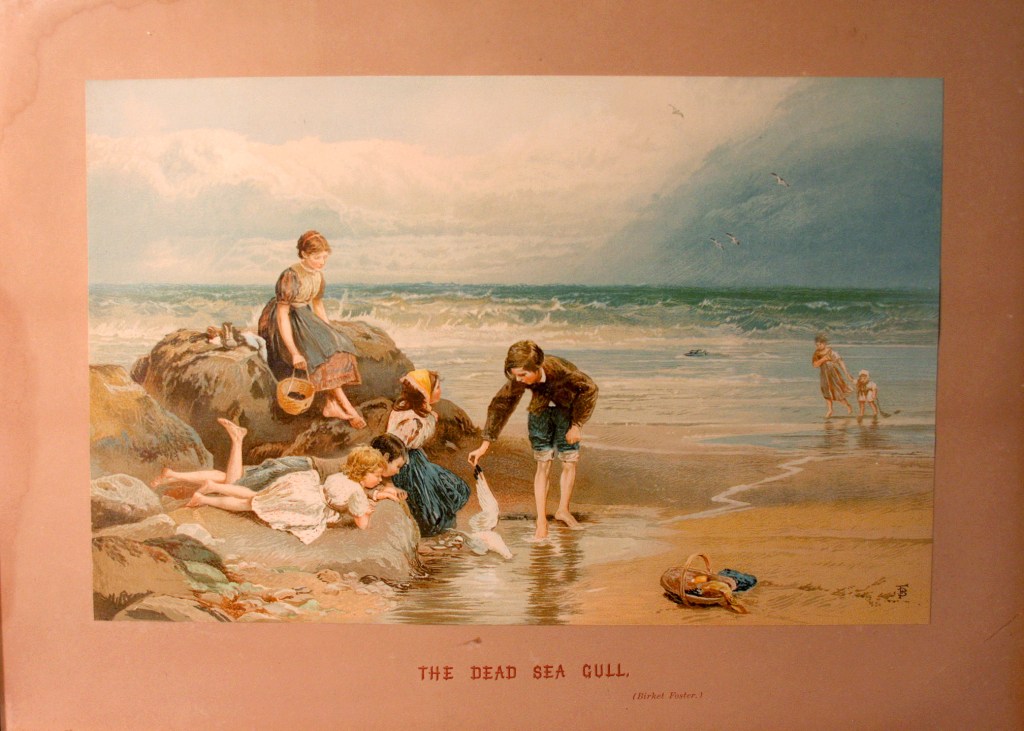

This is a lithograph by Myles Birket Foster (1825 –1899), a British Impressionist. He was one of the most popular watercolor artists of his time, and his idealized, sepia-toned prints and paintings were reproduced on the cover of various magazines and books.

The lithograph belonged to one of our grandparents and we found it in a box of discarded items in a storeroom. Dating back to the British colonial era in South Africa, this kind of naturalistic and idealized print was very popular, evoking a sense of connection with England.

Lilian and I like it because it evokes memories of our own childhoods on South African beaches more than seventy years ago. We would spend hours wading in the rock pools at low tide, picking up shells and pieces of seaweed, scattering the very small fish that were trapped there when the tide went out, picking up a seagull feather, or chasing a crab: All the time under the watchful eye of a nearby mother. We might as well have been under the watchful eye of Birket Foster as he sketched the scene.

What is it about the ocean that makes such a strong impression on people? In the following diptych a young woman sits on the beach and immortalizes the experience by writing how she feels on the back of the photograph that was taken by her fiancé.

The woman is my mother, and the year is 1940 in Cape Town.

Thirty years later, another diptych:

This is Lilian, fifty years ago.

And now, a triptych:

A granddaughter on the beach in Barbados.

Seventy percent of the earth’s surface is ocean, yet most of us experience it in a personal way with a heightened sense of the here and now. Yet, there is a universality in which we all share. This is illustrated, perhaps, by my five-panel polyptych:

The photographs comprising this polyptych include images of the Pacific, North Atlantic and Indian oceans, as well as the Ionian and Caribbean seas.

Continuing with the ocean theme, I created the following image using separate images of hands and the ocean that appeared in a single issue of the New York Times. The viewer is naturally free to find any personal meaning that it may evoke:

But to return to the more tranquil experience of the ocean, here are two images. The first, a photograph I took and manipulated, not by the ocean but on the shore of Lake Erie, one of the Great Lakes.

Finally, a drawing by Edvard Munsch of his younger sister, Inger, seated on a rock beside the ocean, an 1889 scene conveying the gentle, contemplative sensibility that we saw in the Miles Foster Birket lithograph with which we started this posting.