My previous post focused on the color blue, so this image provides a nice transition from blue to this post’s subject, something white. The photograph was taken in White Sands National Park in New Mexico and is completely surrounded by White Sands Missile Range. The white material in the photograph consists of gypsum crystals, and the dune field is the largest of its kind on earth. Fossilized footprints found here are dated to the earliest arrival of humans in North America around 20,000 years ago.

For some, the color white is a symbol of innocence, purity and peace. It is ironic and sad that this beautiful place is surrounded by a missile range where instruments of war are tested.

This Gardenia blossom surprised me as I walked past a small tree in the Louisville Zoological Gardens. Native to Asia, Gardenias were introduced to the southern United States in the 18th century but are relatively uncommon in Kentucky. The last time I had seen one was in the 1960’s in South Africa. To make sure that this was a Gardenia, I stepped closer to smell it. Yes, the intoxicating fragrance confirmed that this was the real thing. The scent of the flower plays an important part in attracting pollinators especially at night, appealing to nocturnal insects like moths who are also attracting to the white flowers discernible in the dark.

Is the image just a pretty photograph, or does it remind you of a time and place? Can you remember the fragrance?

Snow is actually translucent or clear because it is made of ice. But, because of the crystalline nature of ice, when light is reflected off the ice crystals, it breaks up and all the colors of the spectrum shine equally. Our eyes perceive all these colors colliding as white. The philosophical and scientific moral of the story is that things are not always as they appear, but in the case of snow let us embrace the appearance.

What does this little sign have to do with Something White? Well, the lacquered white base on which the black letters are printed is white. The hand that holds the sign is White. The second line is written in Afrikaans. Translated, it reads “Whites Only”. That’s how things were in South Africa before the end of apartheid. Our small group of anti-apartheid activists removed these signs from park benches in the city, an inconsequential gesture that may not have even been noticed. But there are times when one cannot remain silent. This was a beginning.

Living at peace with our Whiteness is not always easy.

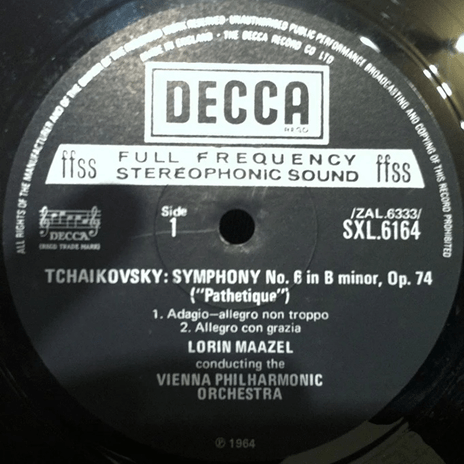

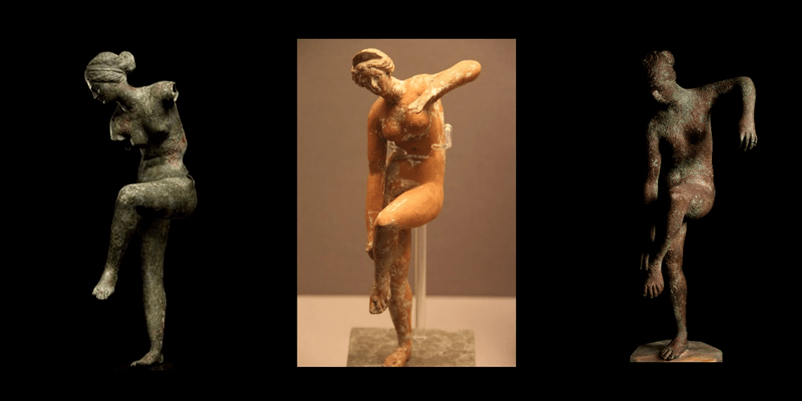

Here is Lucy who brought much happiness to Lilian and me during our retirement. We have been “dog people” for most of our lives with canine members of our family that include golden retrievers, labradors, border collies, spaniels, and an assortment of mixed breeds. But it was Lucy who stole our hearts. Maltese dogs have a rich history that dates back over 2,500 years, originating on the island of Malta. They were popular in ancient Greece and Rome (catuli melitaei) and were even linked to the goddess Venus who was said to have kept them as pets. We like to think that Lucy is now with Aphrodite on Mount Olympus.

When one starts to think about white, a person becomes more conscious of it in our everyday lives. In the diptych above we see toothpaste and facial tissue. In much of Africa, the word for toothpaste is “Colgate” and in the United States and Canada, the word for facial tissue is “Kleenex”. Good examples of metonymy, the phenomenon that occurs when a brand name is so widely recognized that it is used in place of the product itself.

This flower can teach us something. It is the Trichocereus Candicans, also known as the Argentine Giant, native to Argentina. It thrives in arid climates and full sun, so it wasn’t surprising that it bloomed in our Sonoran Desert home. It is a night flowering species and although it blooms for only two days, it leaves an indelible impression. May our two-day lifespan leave its own beautiful mark.