This morning it was -3 F (-20 C), unusually cold for Northen Ohio on the shores of Lake Erie and a good day for staying at home and enjoying some of the art and artifacts that we’ve collected over the years. One of the benefits of blogging about these things is that it makes one look more carefully at them and appreciate them anew.

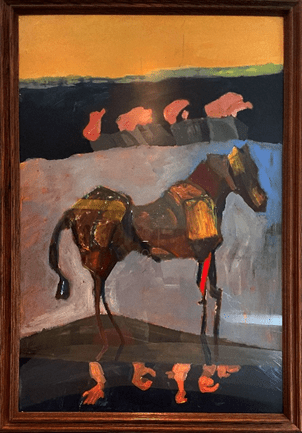

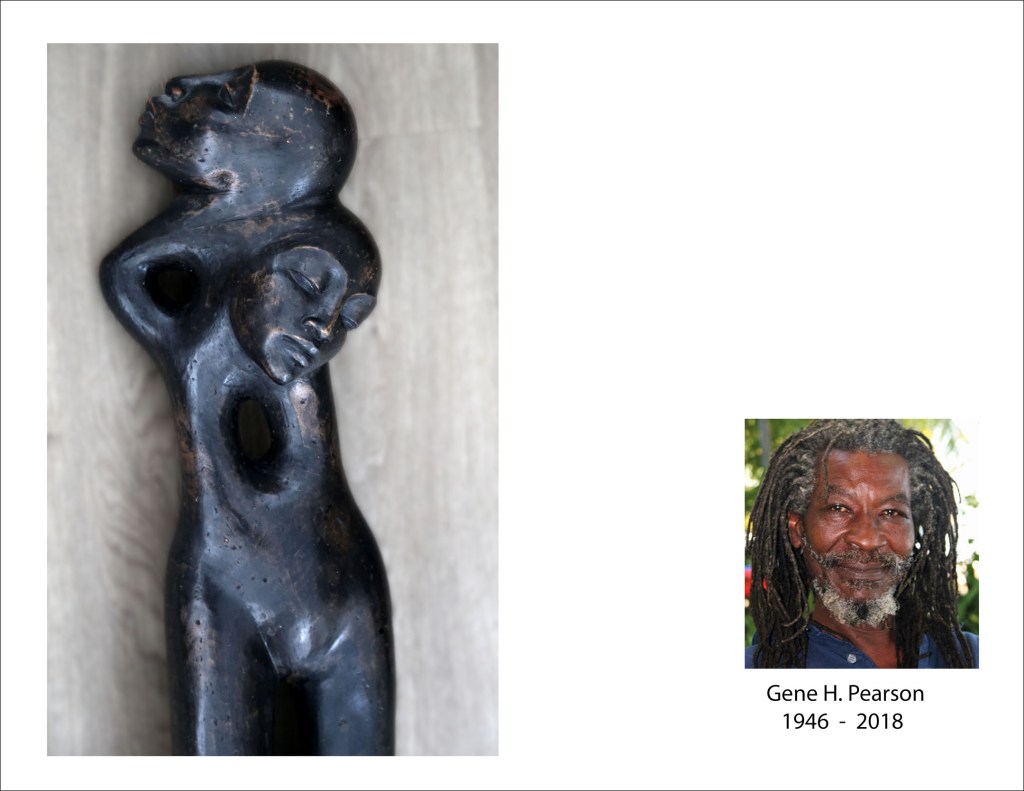

The Dancers, Gene Pearson, Harmony Hall, Jamaica, 1985

We bought this 60 cm high ceramic sculpture 40 years ago in Jamaica when we lived there. Gene Pearson was one of the earliest students at the Jamaica School of Art, returning in 1970 to teach ceramics for ten years. Based in Kingston, his work has been exhibited widely including at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and UC Berkeley in Berkeley California. We were drawn to his signature Nubian masks and heads for which he became known internationally. We had mixed feelings about the strange superimposition of two heads one body. Yet, the individual heads were so expressive, we couldn’t resist acquiring the sculpture.

Nearly forty years later and 2.500 miles distant, we were attracted to another ceramic piece of art.

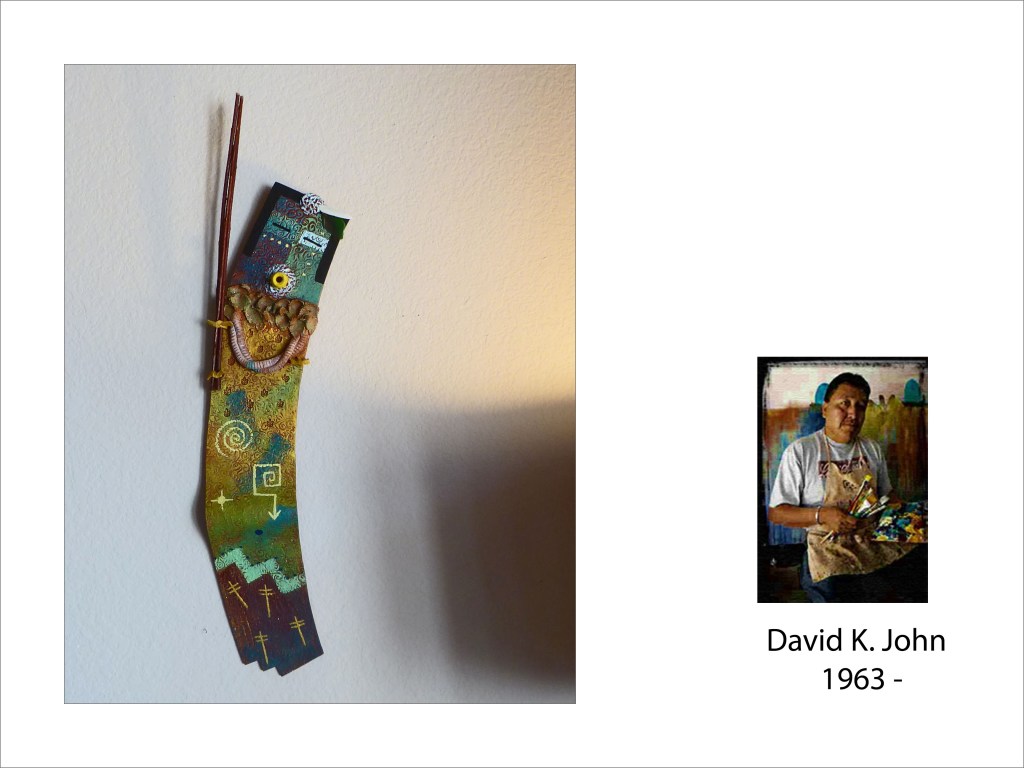

Born in 1963 in Keams Canyon in the Navajo Reservation, Arizona, David John is best known for abstract Indian symbolism painting, sculpture, and ceramics. Soft-spoken and humble, John admired his Grandfather, a medicine man who instilled profound, spiritual beliefs in the young Dine. John spent much of his childhood attending healing events-from seasonal rituals to sand painting ceremonies where he often participated and was instructed by the most revered members of his culture.

John is specific about his use of color. Like most native American tribes, the Dine (Navajo) associate particular colors with the four directions: yellow-the west, white- the east, turquoise-the south, and black- the north.

John’s characteristic messenger is the Yei Be Chei, an ethereal messenger to the Navajo. Since exact replication of the sacred icon is taboo, he modifies the image to the satisfaction of his tribe’s spiritual leaders. According to collectors, the alteration does not affect the impact of the painting’s message.

Looking around the house, we find more ceramic works but in very different genres.

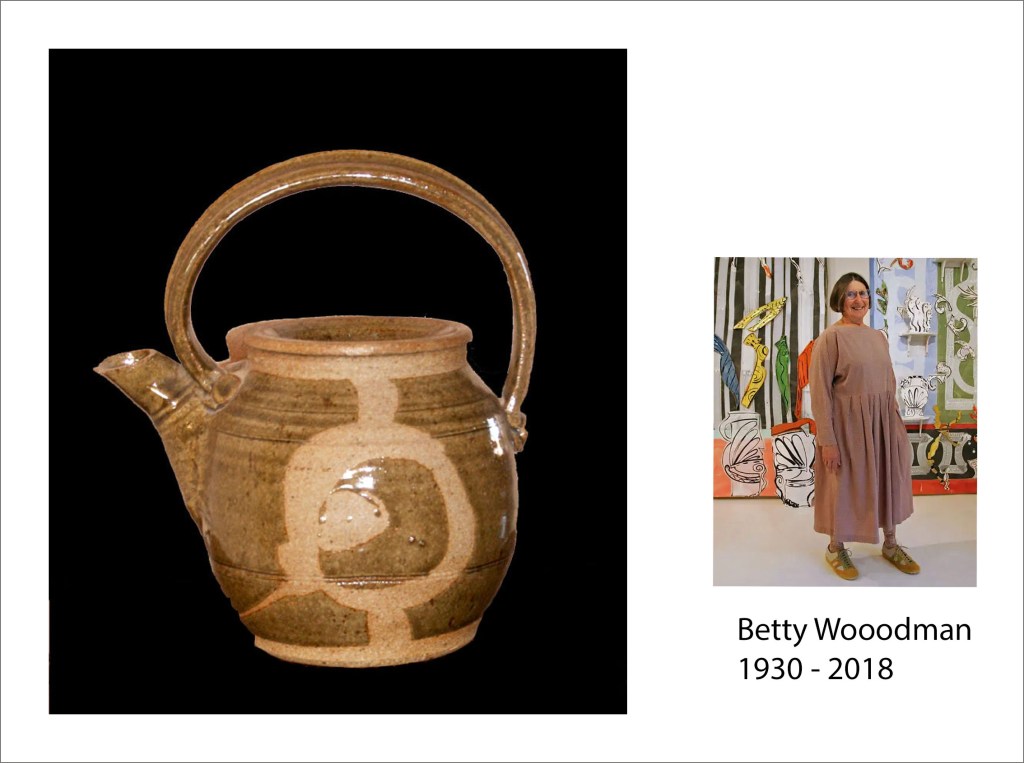

Tea Pot, a gift from Aunt Betty in 1969.

In the 1970’s, Betty’s work took a new turn as she deconstructed the traditional ceramic household vessels. “I make things that could be functional, but I really want them to be considered works of art.” And, increasingly it seemed, she moved from three-dimensional objects to flatter two-dimensional ceramic pieces.

Betty Woodman, Vermisage, MaxProtech Gallery, NY., 2006

Betty Woodman’s evolution from artisan to fine artist as illustrated in the two preceding images, culminated in a retrospective in 2006 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, its first for a living female artist.

Elsewhere in the house, we find a vase, the work of a Canadian acquaintance from thirty-five years ago.

Margaret Hughes, Kingston, Ontario, 1990

Here is a good example of what Betty Woodman was talking about: The deconstruction of a household item that, while still possibly serving a functional purpose, is an expressive work of art.

And, while on the subject of ceramics, I should include another object that we have sitting on a mantlepiece.

‘Cawl” or soup bowl, Llanelli Pottery, Wales, 1839 – 1922

The bowl, a gift from a grandmother, was likely made in the early 1900’s. ‘Cawl’ was the staple diet for families in the country. It consisted of a clear soup made of boiled meat, vegetables and chopped parsley. The bowl has a pleasing form, decorated with attractive sponge imprints. The pottery made in the factory at this time was of poor quality, tending to ‘craze’ into fine cracks.

I hear the furnace turn on, reminding me of the cold outside, and looking out the window, I see starlings at the feeder, undeterred by temperatures below zero.